Hello and welcome to the second edition of Heroes of the Lost Age!

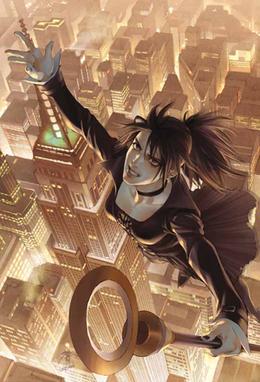

Our new lost hero explored is...Night Man!

Night Man made his comics debut in The Strangers #1 and Night Man #1, created by Steve Englehart and Rick Hoberg in 1993 as a part of the Ultraverse imprint of Malibu Comics. What's the story you ask? Night Man is about Johnny Domino/Domingo, a jazz musician operating in the Bay Area, until a cosmic event called "The Jumpstart" endowed him with the power to hear evil thoughts of others around him, and to see in the dark. At the cost of his ability to sleep.

Armed with this new ability, Domino put together a costume to fight criminals as the Night Man.

The character has undergone certain changes as to his powers and development. In the second relaunch of the comic book series, Night Man had his powers altered by Rhiannon, enabling him to see a dark aura around people, generate lightning from his hands, fade into the darkness for stealth, and being mentally linked to a dagger that was bestowed upon him by Rhiannon which he can sense from a distance and cut portals in the air for teleportation. But Rhiannon's gift came with a cost, Night Man must consume a broth of human organs in order to survive.

In 1995, Night Man made his TV debut in the old Ultraforce cartoon. In the episode "Night and the Night Man", his origin is told in the same fashion as the comic book. When Johnny is turned into an Ultra like others involved in the accident, team members Hardcase and Contrary try to recruit him to their ranks as their adversary Chrysalis terrorizes San Francisco.

Though it was declared official Malibu Comics had fallen by their being purchased by Marvel Comics in 1995, Night Man would make his presence felt once more in a live action TV series starring Matt McColm as the title character from 1997 to 1999. The series was created by Glen A. Larson.

In contrast to the comic book incarnation, Night Man's origin is told differently as to not being called an "Ultra." He's struck by a bolt of lightning in a freak cable car accident which gives him his powers. Although he battles a different villain in each episode, Night Man's arch enemy is computer billionaire Kieran Keyes (Kim Coates) who would kill his father in the premiere of the second and final season.

The TV version of Night Man is painted in a different light. Instead of a makeshift costume he put together himself, a tech wizard gives him a bulletproof body suit which enables him to fly with an anti-gravity belt, a camouflage invisibility mechanism, and advanced sight functions in the lens over the left eye of his mask that allows him to fire a laser beam. Like his comic incarnation, this Night Man could see in the dark.

In retrospect, Night Man appealed to me in my youth. Being a superhero fan I didn't care how the TV show looked since I enjoyed Spider-Man, Batman, and X-Men when they had their own animated series respectively. What fascinated me about him was how he's different from the others. He's a musician playing a mean saxophone. And though Night Man possesses a telepathic power, he's trained in aikido which he utilizes in his endeavors to make him a grounded character. With the Ultraverse in the hands of the House of Ideas, those who remember the characters like Johnny/Night Man should hope for a comeback from limbo.

That's all for our Heroes of the Lost Age! Tune in next time!

_poster.jpg)